Principles

Complexity lens

Clockware/ swarmware

Tune to the edge

Competition/ cooperation

Bibliography

Hurst & Zimmerman: Lifecycle to Ecocycle

From Lifecycle to Ecocycle:

Renewal via Destruction and Encouraging

Diversity for Sustainability

Brenda Zimmerman,

Schulich School of Business,

York University,

Toronto, Canada

| The basic idea: |

Drawing from biological systems, the ecocycle also suggests a need for a

"healthy" organization or system to have parts (or aspects) of the organization

in every phase of the ecocycle. Diversity in the phases of ecocycle is crucial for the

sustainability of a complex adaptive system.

| Potential context for use: |

- To identify things that you should stop doing in order to support the renewal of the work (or of health care)

- To recognize when you are complicit in perpetuating the very things you know need to be stopped

- To redirect energy and reallocate resources to activities that support renewal and change.

- To determine the skills and attributes needed for a management team, board of directors or project team.

- As a contingency framework, to determine which techniques or approaches are needed for different phases of work.

- To encourage diversity in the stages of the ecocycle by recognizing that healthy organizations or systems exhibit all phases of renewal, birth, maturity and destruction.

In this aide, the description

section is used to give some background to the ecocycle concept. The facilitator’s

tips section outlines four specific ways to use the ecocycle in organizations. The

examples section follows the facilitator’s tips and provides two situations where

deliberate use of the model have been helpful for organizations facing major changes in

their environments.

| Description: |

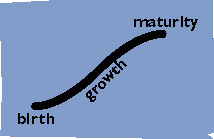

The lifecycle model of

organizations has proven useful to understand the growth and maturity of industries and

organizations. It has been called the S curve in business schools. It depicts the birth,

growth and maturity or a business or industry.

However, the S curve has failed

to address other aspects of living systems: their death and conception, in other words the

phases of destruction and renewal. The model is silent on these aspects of a true life

cycle. The ecocycle extends the lifecycle concept to incorporate these dimensions. The

evolution and sustainability of complex adaptive systems includes the natural and

necessary roles of destruction and renewal. The paradox is that renewal and long term

viability requires destruction.

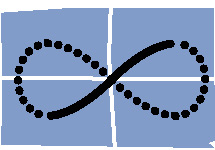

The ecocycle concept is used in

biology and depicted as an infinity loop. In this case, the S curve of the business school

life cycle model is complemented by a reverse S curve. It is the reverse S curve, shown

below with the dotted line, that represents the death and conception of living systems. In

our depiction of the model, we call these stages creative destruction and renewal. The

importance of the infinity loop is that it shows there is not beginning or end. The stages

are all connected to each other. Hence renewal and destruction are part of an ongoing

process.

Being an infinity cycle, there is

no obvious start or end to the cycle. Let us begin our examination of the stages at the

beginning of the traditional S curve. We will begin each phase by using the biological

example of a forest and then look at the analogous phase in human organizations.

Principles

Multiple actions

Competition/ cooperation

The

lower left-hand quadrant is the birth and early stage of life phase. This may be an open

patch in a forest. This state is characterized by a wide variety of species all competing

for the resources. There is usually not one dominant species. There are a lot of births in

this stage, however, many of the new births do not reach maturity.

In human organizations, this is

the early "entrepreneurial" phase of an industry or organization. This is a

period of high energy, lots of new ideas and trial and error learning. Resources are

spread over a variety of projects or activities.

In the forest, after a while the

open space becomes crowded, competition starts to require efficiency. Fewer species are

supported as the resources become consolidated or conserved in a few trees that begin to

dominate the space. This maturity or conservation phase is the upper right hand quadrant

on the ecocycle.

In human organizations,

travelling up the S curve from the lower left-hand quadrant to the upper right hand

quadrant has been the mainstay of business wisdom for the past 50 years. Strategic

planning, budgeting and most control systems are designed for this process of

consolidation and improving efficiency. Streamlining operations and allocating resources

with more predictable returns is good management as you move through this phase.

Reflection

Metaphor

We

now move to the reverse S curve as we move to the lower right hand quadrant. This is the

phase of creative destruction or in our forest analogy: the forest fire. The system is not

fully destroyed. But this is not obvious to the naked eye. The burning of the trees and

dead wood releases nutrients and genetic material into the soil to create the conditions

for new growth.

In human organizations, the

creative destruction phase may require dismantling systems and structures that have become

too rigid, have too little variety and are not responsive to the current needs of the

community (or market). An additional level of difficulty in human organizations is the

consciousness of the participants who may cling to the old ways because they were the keys

to success as they moved up the S curve. This can be a very disturbing, unsettling time

for organizations as assumptions need to be exposed and re-examined in light of changing

needs and environments. However, the creative aspect of the creative destruction phase

also indicates the potential for this to be a period of high innovation and new insights.

The quadrant in the upper left

completes the reverse S curve and the ecocycle. This is the mobilization and renewal

phase. In a forest, this is the phase after the fire where open spaces have now been

created. The soil is rich with nutrients and the number of possibilities of how these

nutrients will be recombined is very great. It is rich with potential but it is not at all

clear what combinations will be most successful.

Tune to the edge

Generative relationships

Stacey matrix

Min specs

Wicked questions

As

the brief description above show, the role of the manager and of the leader change

radically when moving up the S curve as opposed to travelling the reverse S curve. The

lessons from complexity science are highly relevant to travelling the reverse S curve.

Looking at a forest analogy, we

learn several things about the ecocycle. First, a healthy forest exhibits patch dynamics.

In other words, a healthy forest has all parts of the ecocycle in evidence. Some parts of

the forest are dense with mature trees. Other parts are open patches in which life is not

obvious to the naked eye. A healthy forest will have areas of new growth with many

species. Finally, there are parts of the forest which are in periods of destruction

perhaps through a fire, flood or disease.

Patch dynamics are healthy for

forests. Yet they look untidy and a bit disorganized. From an aerial view, the unbroken

blanket of mature trees may be more aesthetically appealing, but history has shown that a

forest in this state is brittle and can be completely devastated by, for example, a fire.

Here is the paradox. The forest needs occasional fires (or other forms of creative

destruction) to renew itself. However, a massive fire can actually damage not only the

trees but also the soil. What this paper is advocating is not a "scorched earth"

policy of wanton destruction. Rather fires or their equivalent in organizations, can be

beneficial if they break down the structures without damaging the soil.

Competition/ cooperation

With

no firebreaks in the forest, there is nothing to stop the path of destruction caused by a

fire. Fire fighters discovered this in the late 1970s and have since changed strategies.

Rather than putting out all fires, they look for situations where they can let a fire

burn. They also deliberately set fires at times. Fire serves as a powerful form of

creative destruction in forests. It burns away the dead wood; it replaces the soil with

needed nutrients and sets the context for the creation of new generations of growth or

even new species. A forest needs to have patchiness to it to ensure its long-term

viability.

The ecocycle uses the concept of

creative destruction and crisis to explain the necessary destruction of forms and

structures periodically to maintain the long-term viability of the overall system. The

word crisis is derived from the Greek krinein meaning to sift. In the ecocycle model, we

think about crises as opportunities to sift so that the unnecessary forms and structures

are removed to enable the substance to be renewed and continue to evolve.

What does this mean for

organizations or human systems? Forms and structures that no longer support the

"work" or the mission of an organization or system need to be destroyed in a

manner that does not destroy the substance. It is a "substance over form"

distinction. Forms and structures are necessary to enable the work to be accomplished but

they are not the essence of the work. In health care, this has become a major issue. The

substance of health care is not the structures of hospitals, clinics or even the

professions of physicians and nurses. Rather these are forms that have enabled health care

work. As enablers, they are crucial but they are not the substance of the work. Forms and

structures must be seen as ephemeral. They support the work but are not the work itself.

Why should health care leaders

learn about this concept? It sounds quite threatening to the medical professions and

institutions. This is a fair assessment, however, it is my contention that this is

happening anyway and it is preferable to be a player in the process to ensure the

substance of health care is not lost but indeed renewed in this period of change. We

return to the paradox mentioned earlier that "fires" can lead to creative

destruction or devastation. Creative destruction is positive and is not synonymous with

devastation where not only are the forms and structures destroyed but the substance as

well. In a forest, a devastating fire has the potential to destroy the trees and the soil.

In these situations, it can take generations before the soil can nurture new life.

Creative destruction is designed to release the nutrients so that new life can indeed

emerge.

In addition, leaders of health

care organizations need to think about whether their organizations exhibit patch dynamics.

Is there enough diversity in the organization to prevent a single "match" from

setting fire to the whole system? Are there firebreaks in the organization? Firebreaks may

take the form of diversity in funding sources so that one funding source cannot determine

the survival or demise of the organization. Firebreaks may also be the

"skunkworks" in the organization, in other words, the parts of the organization

which are trying out new ideas and approaches uninhibited by the "way things are done

here." This is insurance for situations when the community, the funders, the patients

or other key constituents no longer support the "way things are done here".

| Reflection: |

Before using this aide:

Will the group be comfortable using biological metaphors (like a forest) to reflect the issues in your organization?

Will the group see this as an unethical approach? Will they trust that this is a process of honest reflection? Can you demonstrate this by applying the model first to your own context before exposing others to the model?

After using this aide:

How can you move the intellectual discussion of application of the metaphor and model into meaningful action?

| Facilitator's Tips: |

Stop doing and complicity exercise

After a description of the ecocycle, post on a flip chart the following two questions:

What do you need to stop doing to focus on (the nutrients or) substance of your work?

In what ways are you complicit in perpetuating that which you say you must stop doing?

Direct the participants to spend 10 minutes addressing these questions on their own. Then direct them to spend 10 minutes sharing answers with their group. For very large groups, you will need to break them into smaller groups. Have each group post on the flipchart the two "best" answers - one for each category - i.e. one for what you must stop doing and one for how you are complicit.

The definition of "best" has to satisfy the "whoa" test. In other words, what made you sit back and go "whoa"? You don’t have to agree with the "best" you simply have to find one that took you by surprise. Maybe it is controversial, maybe it is gut wrenching, and maybe it is challenging or outrageous.

Post the flipchart on the wall when you are finished. Use these for discussion purposes and coming to some agreement on what the group will stop doing.

It is crucial that the complicity side of the exercise is completed. Without it, it is too easy to say that what must be stopped or changed is someone else’s responsibility or domain. The purpose of the exercise is to uncover how your own actions need to change to enhance the renewal of the work. Recognizing your own complicity in maintaining the status quo is a critical first step.

Substance over form exercise

Suggest individual work for 20 minutes. Since they will not be sharing this with others, they can be brutally honest with themselves.

Take a sheet of paper and draw a vertical line down the middle. On one side of the line write, "form" and on the other write "substance".

Think about your work. What aspects of your work are form and what aspects are substance? As you enter something on the substance side of the page, ask yourself if there is any way this could be form. Could there be something more substantive that underlies it (i.e. try to go as deep as you can on the substance side).

Ask yourself what forms or structures need to be abandoned in order to focus on the core substance or purpose of your work?

Patch dynamics exercise

After a reading of the ecocycle article or a discussion of the need for patch dynamics in the organization, ask the participants to map out the various activities on the organization on an ecocycle diagram.

One way to do this is to identify some of the key activities, programs or projects of the group in question. Have participants put the activities on post-it notes. On a large flipchart draw the ecocycle as background. Post the flipchart on a wall. Direct participants to place their post-it notes on the diagram.

The differences can open up conversations about how people view different programs, their implicit assumptions about the environment and strategic directions.

Have people listen to each other’s ideas and move their post-it notes if their perspectives have changed.

After the discussion has taken its course, say 30-60 minutes, look at the map drawn. Is there a sense of healthy patch dynamics in the organization? Does the map show areas where there is little emphasis? Does this indicate the need to redirect energy and resources in these areas?

Often what happens in this exercise is that an organization will be depicted with a dominance in the mature or conservation phase of the ecocycle. In those cases, it is often useful to reiterate the argument about firebreaks and the need for them as protection against massive devastation. Ask the participants to identify the firebreaks that currently exist in the system. Then ask them how they can put more firebreaks into their system. Ideally, you would like them to identify where these firebreaks are most needed and suggest next steps to implementing them.

Stacey matrix

The problem is that what made

an organization or system successful on the rise from birth to maturity often is the

opposite of what is needed for the creative destruction and renewal phases. The expression

"nothing fails like success" fits here if the management and leadership do not

adjust for the change in the stage of the ecocycle that the organization is facing.

As a facilitator, ask

participants to identify some of their most successful programs or services. Ask them to

map them on the ecocycle. Direct the participants to explain the critical success factors

of the program(s). Then ask them how these critical success factors could become critical

failure factors if the environment changed. Is this happening now? Where? What does this

suggest for alternative management and leadership approaches? (If the alternatives needed

are for more work on the reverse S of the curve, then look to other aides in Edgeware for

guidance or suggestions.)

The purpose of this exercise

is to explore how the success factors of the past can blind you to the needs of the

future.

| Examples: |

In this section, I provide

two examples of the ecocycle aide in practice. The first relates to leaders of

organizations who, using the stop doing and complicity exercise, became

"unstuck" in their leadership role. The second example tells the story of how a

board realized that it needed more capacity for creative destruction and renewal and

deliberately recruited new board members to fulfill this need.

Example 1:

Leaders of social service agencies stop doing and

get moving.

In late November 1996, I

facilitated a meeting with close to 100 leaders of social service agencies. We did the

"Stop doing and complicity exercise." These organizations were facing similar

contexts of decreased government support, increasing demand for their services and

exhausted employees.

In response to "what should

we stop doing", the following are a few of their answers:

- practicing impression management

- taking control of everything

- fighting with funding sources (especially about how to implement programs)

- reacting to negative energy

- being seduced by matters of false importance e.g.

paper work

putting out all the brush fires

negative thinking

old grievances

There was a strong sense in the

meeting that these were common issues across the agencies. Before doing the complicity

side of the exercise, several of the CEOs expressed frustration that these realities were

unchangeable by them.

I then asked them to think

carefully about the lists that had been generated and take a hard look in the mirror to

reveal the ways in which they had been complicit in perpetuating the problems.

In response to in what ways are

we complicit, they generated long lists of ideas. Some of these are listed below:

- rescuing or protecting others from change

- taking things personally

- feeding into negative energy by not countering proactively with something positive

- condoning negativity with silence

- avoiding talking about the real issues (need instead to do the "5 whys")

- assuming too much responsibility

- keeping information to ourselves

- believing I am indispensable to the organization

When we debriefed the exercise,

participants commented that there was a paradox in the complicity part of the exercise.

Recognizing one’s complicity in the problems was humbling but at the same time

energizing. The leaders were all comfortable taking action and yet had felt frozen in many

ways. By recognizing their own part in the problems, they had specific things they could

change. In addition, they commented on how it was great to be thinking about what they had

to stop doing rather than adding to their to-do lists.

Since then, several of them have

spoken to me about the changes they have made. They commented that they are far more

selective about what meetings to attend. They said they find negative energy far less

threatening because they felt they didn’t need to own it or work with it. They also

found their role as leaders had both expanded in scope at the same time as they were more

willing to delegate real responsibility.

Example 2:

An organization brings creative destruction

and renewal to the board.

A board of a nonprofit

organization worked with the ecocycle to reveal what management and governance practices

were needed to address changes in their context. The organization was facing competition

for its services from all three sectors: other nonprofit organizations, government

agencies and for profit businesses. The organization needed to rethink their identity and

role in a context of increasing competition for a shrinking pool of financial resources

and increasing demand for their services in the community.

Wicked questions

Generative relationships

Realizing

that their success to date had been due to skills at riding up the S curve, they saw their

current needs were radically different. One of the changes they made was to change the

criteria for board members. They saw that to go through the creative destruction and

renewal phase, they needed skills in the areas of building generative relationships (often

with organizations and sectors they had not previously interacted with to any great

extent), thinking about the issues systemically, and capacities to make sense of complex

information. They looked for board members who were diverse in backgrounds and experience,

shared a passion for the mission of the organization but were not committed to the

institution itself. These new board members were willing and able to make connections with

people and organizations to rethink how the substance of the work should be done. In

essence, the organization brought the capacity for creative destruction and renewal into

the board.

Principles

Good enough vision

About

three years into this process, the board was faced with a 25% cut to its funding. With the

help of the board and with the explicit use of complex adaptive systems thinking, the

organization survived and has now (almost three years later) returned to its original

size. However, the organization is radically different in form than its predecessor. What

was once one organization is now two. The tasks and programs for the most part are

substantially changed from those offered six years ago. What has remained unchanged is the

focus and passion for child welfare and prevention of social, economic and health problems

for children.

One interesting footnote to this

story, is the organization in question found CAS thinking so valuable for its own

purposes, that one of its new services is a consulting practice for other nonprofit

organizations based on the principles of CAS.

References for further study:

For further elaboration of this

concept see "From Life Cycle to Ecocycle: A New Perspective on the Growth, Maturity,

Destruction and Renewal of Complex Systems," by David Hurst and Brenda Zimmerman, Journal

of Management Inquiry, Vol. 3, No.4, 1994, pp. 339-354

Also see Holling, C.S..,

Simplifying the complex: The paradigms of ecological function and structure. European

Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 30, 1987, pp. 139-146

D.K. Hurst, Crisis and

Renewal: Meeting the Challenge of Organizational Change, Harvard Business Press, 1995

Next | Previous | Return to Contents List

Copyright ©> 2000, Brenda J.

Zimmerman. Schulich School of Business,

York University, Toronto, Canada. Permission to copy for educational

purposes only.